- Losses are not the only risk investors face

- What is risk management?

- How to expose unknown unknowns

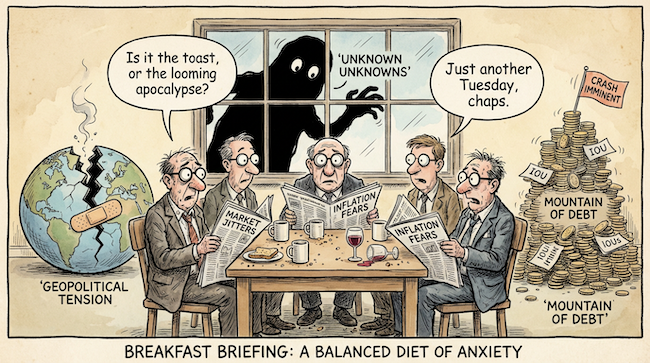

Stock markets go up and down. Inflation fluctuates too. Stock market crashes can happen. But what investors should really fear is a risk they don’t see coming. Sometimes, they don’t even know it exists.

US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld called these risks “unknown unknowns.” The kind of risk that’s difficult to prepare for because you don’t know what they are yet.

Today, I want to show you that we are in a new era. One of unusually frequent occurrences of unknown unknowns in financial markets. Things we never even considered plausible are happening ever more frequently.

That’s because a large number of unusual things are true today. Some are even unprecedented…

We have never experienced demographic shifts like today. We don’t know what they’ll bring. Even history isn’t much help.

Geopolitics is making long-forgotten problems like war in Europe come back. Investors don’t remember how to deal with them.

Globalisation is reversing, or fragmenting trade relationships.

The political shift towards right-wing and libertarian policies in some countries is unfamiliar to many investors alive today. We’ve been through decades of left-wing creep.

Two-party systems are shifting towards four-party systems in many politically stable countries.

Government spending as a share of the economy is exceptionally high, so politics has an unusually large influence on financial markets.

We’re in an era where money printing is very much on the table as a policy tool. That would’ve been considered absurd two decades ago.

Valuations in housing and stock markets are extreme. Historically, that has been followed by very poor returns.

But governments are buying into businesses and projects to secure access to resources and manufacturing. Does this change anything?

Perhaps most important of all, government debt is back to extreme levels.

The level is so high that bringing it back down is a major priority for political systems. But few investors have lived through such a time. Rising stock markets have been a priority for politicians instead.

The list of unusual forces is vast. And so investors need to begin doing one of two things. They need to improve their understanding of these unprecedented risks. And they need better risk management practices.

What is risk management?

Risk management in investing is noticeably agnostic about what the risk actually is. That makes it useful for dodging unexpected risks.

Diversification, for example, is about spreading your assets out. This has to be true across geography, industry, asset class and more.

But why do we do it?

Investors don’t know which African despot might nationalise a mine tomorrow. If they did, they just wouldn’t invest there.

We diversify specifically because we don’t know what is going to happen. And so that form of protection works for unknown risks too.

Natural gas traders limit their position sizes in commodity markets as a risk management tool. They don’t know whether an unexpected winter storm or the invasion of Ukraine will spike prices. It doesn’t matter which one occurs for their position sizing to be an effective risk management tool.

We just know that something might happen. Something which moves prices. Risk management ensures you are able to survive it.

Of course, this sort of agnostic risk management can actually cause financial crises too…

Agnostics beware

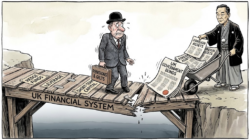

In 2008, investment banks used a risk management tool called “value-at-risk” to ensure their trading positions didn’t get too big.

But VaR was calculated using historical volatility. It presumed the past would resemble the future.

Sometimes, it doesn’t. Sometimes a period of low volatility is actually a warning sign of chaos to come.

So, even the most sophisticated risk management isn’t enough. You need to remain alert to predictable crises based on logic and reasoning. Not to mention historical examples of what can go wrong.

But the point is that your risk management can be agnostic over what shape a crisis actually takes.

Then, when an unexpected crisis occurs, you’re just as well protected as for one that really was somewhere on your bingo card.

How to know what you need to know

You might think that successful investors find out information that allows them to make a successful prediction.

But markets rarely offer that sort of opportunity. By the time something is known with certainty, it is priced in. You can’t make money off it coming true anymore.

A better way to profit is to seek out unknown unknowns. To make them known unknowns. Something still uncertain, but understood by you.

Let’s look at an example…

Did you know about sub-prime mortgages before 2008? Collateralised debt obligations? Special Purpose Vehicles?

And yet, they blew up your wealth.

After the financial crisis, the prestigious academic Luigi Zingales began to point out something shocking. The financial crisis wasn’t really caused by the many things that people blamed. Securitisation, sub-prime loans, leverage, a lack of regulation, or any such scapegoat.

The real problem was simple mortgage fraud. People lied about borrowers’ financial circumstances on loan applications. But they did it on an industrial scale.

We never found out just how bad the problem was. It’s logistically impossible to sift through people’s loan applications and compare the data to their actual financial circumstances at the time – often years ago.

But Zingales’ point was that it is plausible that all other aspects of the financial system were not actually at fault. They just presumed the loan information to be true.

The securitisation of sub-prime loans may have been perfectly sound had those sub-prime loans been made based on accurate information.

Bank leverage may have been perfectly reasonable if those loans had been honest about their borrower’s capacity to repay.

But how do you uncover large-scale mortgage fraud? No investment banker is going to spend their time doing it.

Those who did bother made a motza because they quickly figured out what was going on. And you can find Hollywood movies about them!

They turned an unknown unknown into something they understood better than anyone. And profited from it in spectacular fashion.

The unexpected risk that wiped out so many people was turned into a known opportunity.

The least liquid investment

Let me give you another example from my personal life.

About twelve years ago, I wrote about investing in wine futures. To make the article more intriguing, I invested a small amount myself.

The wine has since matured. A year ago, I tried to sell it at a small profit.

But someone, somewhere, made a mistake on the shipping paperwork. They listed the receiving storage warehouse as the recipient of the wine itself. And so the wine has been stuck in customs purgatory since.

There is no prospect of getting it out of the bond house. An entire team from four different companies have been trying to get the shipping company to adjust their invoice for 12 months now.

The wine’s value is falling fast.

No wine investor would consider the risk of a shipping invoice being filled out incorrectly as a source of investment risk. And yet, it has utterly dominated my returns. Or lack of it.

I didn’t foresee the risk one bit. And it’s changed how I think about investment risk going forward.

Worrying about the wrong things

Financial market historian Russell Napier has been warning people to worry about unknown unknowns for years. He cautions people about “asking the wrong questions.” Meaning we’re worrying about the wrong things.

He believes we’re in for an era of financial repression. That’s a combination of two things. Inflation higher than bond yields. And capital controls to make it difficult to escape this miserable state of affairs.

But it’s just one example of a surprise people don’t consider. Napier has come up with a way to combat our ignorance over what else may be coming. You should read financial history.

Having a longer “memory” means you’ll be alert to the sorts of risks most investors never ponder. And yet, they’ve occurred in the past.

One man who has rather a lot of expertise in anticipating risks no one else even considers is my fellow editor Jim Rickards. After all, he’s been caught up in some of the most extraordinary examples of them.

He was involved in the LTCM meltdown and bailout. As well as the US government’s attempts to predict terror attacks using financial markets. Apparently the sponsors of terror can’t help but dabble in the market before causing a boom elsewhere…

Rickards uses his inclination to question everything and research it himself as his competitive advantage. And it’s been working rather well lately.

Indeed, exposing risks you aren’t worried about, but should be, is pretty much our job. After all, they usually have a corresponding opportunity.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Editor at Large, Investor’s Daily

PS: One of the biggest mistakes investors make in periods like this is obsessing over the risks everyone can already see… while missing the ones quietly forming underneath the system. That’s exactly why this briefing matters. It focuses on a structural shift most markets are still ignoring, tied to real, physical assets the U.S. government is only just beginning to unlock. If you want to see how a hidden risk can also become a rare opportunity, this is worth your time.