CES 2026 is in full swing, with its usual blaze of powerhouse keynote announcements, mind bending next-gen consumer tech, and gigantic doses of optimism.

CES 2026 is in full swing, with its usual blaze of powerhouse keynote announcements, mind bending next-gen consumer tech, and gigantic doses of optimism.

And Nvidia’s CEO, Jensen Huang, is dominating CES headlines right now.

On stage, he rolled out a barrage of announcements, including the Vera Rubin platform, a six-chip “AI supercomputer,” a new Alpamayo autonomous driving stack, and what he calls a “ChatGPT moment for physical AI” as humanoid robots edge closer to the real world.

I’ll be writing more about these things over the next few weeks, but today’s focus is on the biggest news out of Nvidia yet…

An innocuous deal that most investors missed because they were neck deep in Christmas festivities.

That deal was Nvidia’s move on Groq.

Why Nvidia needs Groq

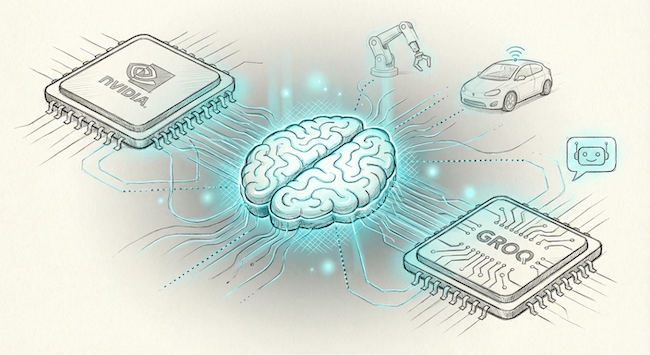

On Christmas Eve, Nvidia confirmed it had struck an agreement with Groq, the nine-year-old Santa Clara-based startup best known for its Language Processing Unit (LPU): An AI chip developed specifically for inference (more on this in a moment).

Officially, this is a non-exclusive licensing deal. But the reality is it’s as close to a buyout as you’ll ever see.

Nvidia will license Groq’s technology and bring its leadership and engineering talent in-house, including founder Jonathan Ross, while Groq continues to operate as an independent company.

Unofficially, the numbers tell a bigger story.

The value of the arrangement is around $20 billion, roughly on par with Nvidia’s landmark Mellanox acquisition in 2019.

This is a hefty rise on Groq’s most recent funding round, which valued the whole company at around $6.9 billion.

Nvidia is effectively securing Groq’s LPU architecture, its compiler stack, and close to 90% of its workforce.

Tell me you bought them out without telling me you bought them out…

So why would the most dominant AI chipmaker on the planet spend $20 billion on what looks, on paper, like “just” a licensing deal?

The answer lies in inference and memory.

It’s all about inference… and memory

Ross founded Groq with a very specific mission: To make AI inference fast, predictable, and efficient.

Not training.

Inference.

Inference is the phase of AI where a trained model is actually used, taking new data and generating an output like answering a question, recognising an image, or deciding how a car should brake.

In simple terms, training teaches the AI, inference is where it thinks, responds, and acts in the real world.

This is critical for Nvidia’s next phase of AI rollout.

Training large models is compute-heavy, sporadic, and expensive.

Inference is constant and requires unimaginable speed.

Every query, every response, every autonomous decision is an inference event. And as AI scales and gets more advanced, there’s an exponential rise in the demand for inference.

I won’t dive into the technical nature of Groq’s chips. If you’re interested, you can check it out for yourself here.

What’s important for you to know, however, is that Groq puts the AI compute and memory on the same chip.

Its LPUs use large amounts of on-chip SRAM (a type of computer memory) to deliver incredible bandwidth compared to traditional GPU (graphic processing unit) designs that rely on external high-bandwidth memory (HBM).

High-bandwidth memory is why stocks like Micron have been ripping higher.

By taking this non-HBM approach, Groq removes the single biggest source of latency in inference workloads… and also the biggest inbound bottleneck for AI compute…

High-bandwidth memory.

Think of it like this…

HBM is like your working memory. It’s the thoughts you’re actively holding right now. A mental whiteboard you’re writing on while solving a problem, if you will. The words you’re about to say next in a sentence.

The higher the bandwidth, the more active thoughts your brain can hold simultaneously without any mental stuttering.

Basically, it’s about how much you can think of all at once, without getting confused or making mistakes.

Even a powerhouse chip like Nvidia’s H100, capable of nearly 1,000 TFLOPS (that’s how fast a computer can think), spends the overwhelming majority of its time waiting for data to arrive from memory during token generation.

Groq flips that on its head. It’s not pulling data from memory. It’s using data that’s already right there in the thought pipeline.

So Groq can generate AI responses much faster and more consistently. That makes it ideal for real-time applications like chatbots, robotics, and autonomous systems.

And that makes the $20 billion Groq agreement chump change for Nvidia.

Moving beyond AI “training”

AI training was 2024 and 2025 news. Inference is the next step, and it’s a different battleground.

Inference chips sell in far greater volume than training accelerators. Higher volume, lower margins, massive demand.

They will exist at “the edge” in cars, factories, robots, and data centres serving millions of users simultaneously.

They’re cheaper per unit, and they’re everywhere.

Whoever dominates inference controls the long-term economics of AI.

By making a play for Groq’s architecture and talent now, Nvidia has taken a big step to locking in the inference market.

Memory, not data, is the new oil

The Groq deal reinforces the theme I’ve been hammering home in Investor’s Daily for months now: AI is running headlong into a memory brick wall.

HBM and next-generation GDDR (that’s the high-speed memory GPUs use to move a lot of data quickly) are already sold out years in advance.

Each gigabyte of HBM consumes far more manufacturing capacity than standard DRAM (short-term memory), straining supply chains that were never built for this kind of demand.

Across the board, memory pricing is still soaring higher, and the likes of Micron, SK Hynix, and Samsung Technologies are all following suit.

This is why the Groq deal is so important. It diversifies Nvidia away from these constraints… and shortages.

It’s a clear catalyst that this year will be dominated by the hardware that inference needs to rip higher.

Companies like Groq – that can provide novel, alternative approaches to inference – will be the goose that lays the golden egg.

That’s why, in 2026, it’ll pay to follow the memory (as well as the money).

Until next time,

Sam Volkering

Contributing Editor, Investor’s Daily

PS On 2 January, I wrote about the shortage in memory and how prices were going up. To get ahead of this, I bought 64GB of DDR5 memory. I was going to sit on it for a year and see how wild prices would go.

Well, how’s this for an update?

I’m currently up around 20% on the DDR5 memory kits I bought.

I also happened to buy a 2TB Crucial PCIe 4.0 NVMe M.2 SSD (storage) for a similar test. That’s up around 32% compared to the price I bought it for.

All of that in about three weeks since purchase.

As I said on 2 January, “maybe physical RAM could be the best investment of 2026.”

So far, it’s looking pretty good!