- Are you on this year’s rich list?

- Cantillon Effects are the most important force in finance

- How to get on next year’s rich list

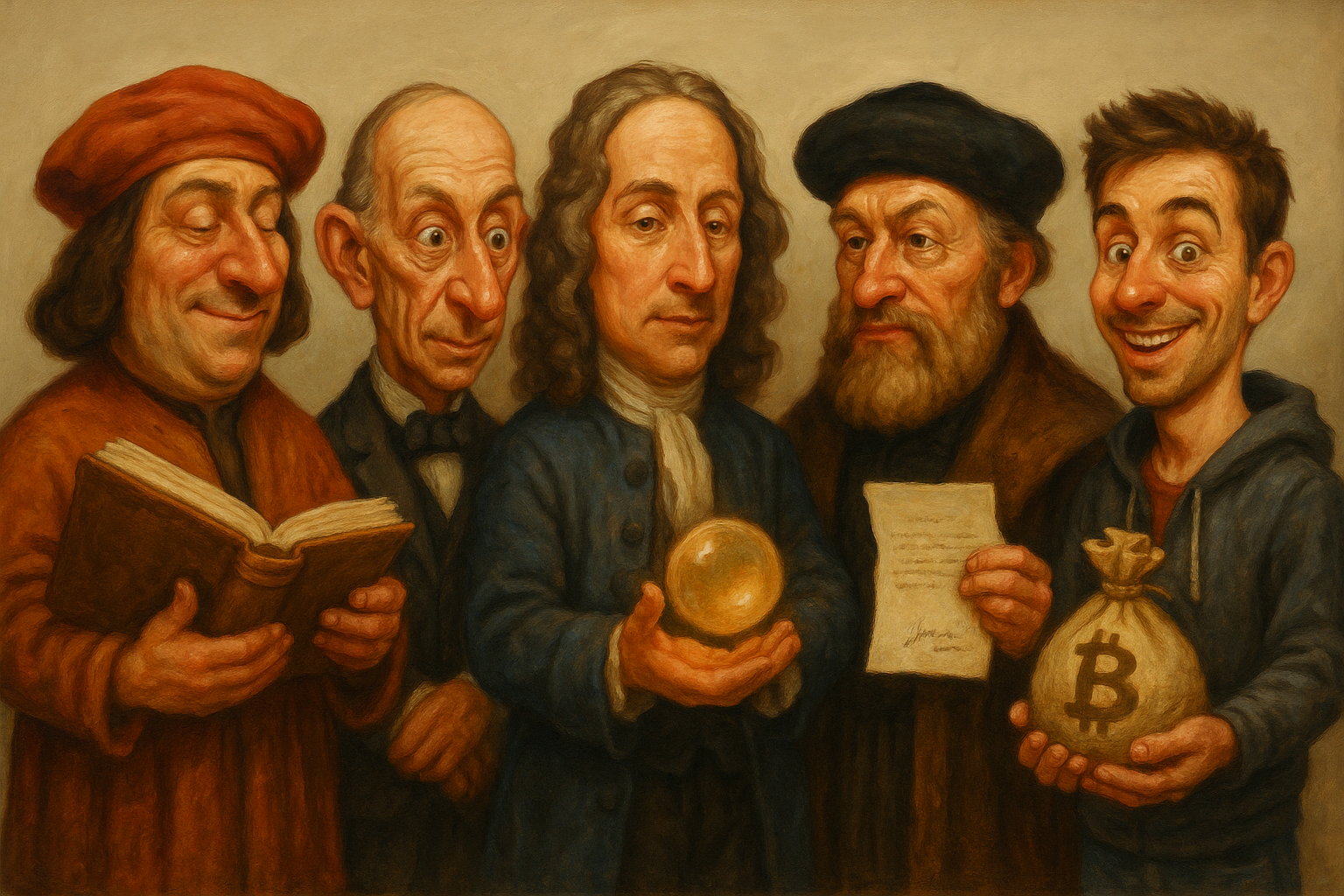

Long before tech unicorns were spotted hiding in every business plan, some families managed to get filthy rich. How did they do it?

Today, I’d like to introduce you to the second easiest way. The first is being born into the right family.

If you didn’t get that lucky, here’s what you need to know to establish your own foothold on a family legacy…

You just need to be born on the eve of a currency revolution. A time when the very nature of money changes radically.

Conveniently for both of us, such a moment is upon us right now. It amounts to a quadrillion-dollar opportunity. One you can harness starting today.

But before we dig into the details, I need to convince you the underlying strategy actually works in practice.

What better way than to show you that the wealthiest families of the last 1000 years followed this path to legendary riches…

Bookkeeping bonanza

The Medici family’s prosperity is legendary. Despite occurring 600 years ago, people still know about them today.

How did they do it? Their fortune was built on a series of banking innovations. When combined, they amounted to a revolution in the nature of money that changed the world forever.

Some of the Medici’s innovations are easy to grasp, such as geographic diversification and foreign exchange trades.

But the Medici were early adopters of the double-entry bookkeeping that still plagues your bank statements today. And they turned banking and the provision of money into a business in and of itself.

Double-entry bookkeeping and a network of branches allowed the Medici to securely move money around Europe in the form of paper promises instead of gold and silver. This made their business dramatically more profitable than their rivals.

Speedy syndicates

The Rothschild family used the same geographic spread strategy as the Medici. They built an even bigger international network of banking brothers who honoured each other’s paper, meaning money.

But their competitive advantage was built on speed and a liquid financial market in government bonds.

Because government bond prices fluctuated based on the news, whoever got the news first could make the most money on the subsequent price moves.

The Rothschilds built a network of information flows that could outpace anything at the time. This allowed them to profit from the major market moves. Including, most famously, the outcome of Waterloo.

The Rothschilds also created syndicates of lenders for governments. This allowed them to offer far larger loans to governments without taking all the risks themselves.

It was a winning combination of financial strategies. And the Rothschild legacy is still around today.

Cantillon captures currency chaos

Richard Cantillon was a poor Irishman working as a paymaster for the army in Spain. From his time observing how the army’s epic spending influenced local markets, he discovered several economic theories. He understood that credit, not metal money, ran the real economy.

More importantly, credit booms and busts could be anticipated and traded for profit. This insight eventually made him so wealthy that he had to fake his own death in a house fire to escape the debtors. Yes, debtors. They who owed him so much money that they preferred to imprison him on false charges, or worse. So goes the legend, anyway.

Cantillon codified his insights into books that, some say, founded the field of economics itself. Economics students today still learn about “Cantillon Effects”. And investors’ portfolios are buffeted by those Cantillon Effects more than ever thanks to fiat money and central bank policies.

The most important Cantillon Effect insight is that money is not neutral. Inflation has very real impacts on the structure of the economy.

The assets and people closest to the source of new money and credit profit the most from its impact. Between 2002 and 2006, this was homeowners in the US, Ireland and Spain, who became rich off loose monetary policy. In 2020, bond owners became rich on QE. And AI stocks benefit from rate cuts today.

300 years before Alan Greenspan learned the lesson the hard way, Cantillon understood that new influxes of money (credit) cause asset bubbles. His method to profit was simple but brilliant: lend into a bubble, secure the loan with valuable assets, collect the collateral when the bubble pops.

Cantillon was also a master of using derivatives like options to profit from stock market booms. His trades were sometimes too successful, leaving Europe’s nobles in impossible debt to him.

Financial Fuggers

The Fuggers may have been the wealthiest family ever, with about £300 billion in net worth about 500 years ago. Not bad for cloth merchants from Augsburg.

But they only became rich once they discovered that financing cloth merchants was far more profitable than being one. From this discovery, many others followed. The Fuggers used double entry bookkeeping and political ties to become dominant in several industries.

Today, money and politics is closely intertwined. But it wasn’t always so. And the Fuggers were amongst the first to establish a connection and profit from it.

The Fuggers’ biggest innovation was what we call “streaming” today. The Fuggers lent money to miners in return for a claim on their future output instead of repayment in cash.

They targeted struggling miners during periods with depressed commodity prices. When prices rose, their share of the ore was worth tonnes.

They used the money to build a trading network. The Fuggers’ Austrian copper made it as far as China. And their wealth financed a Holy Roman Emperor’s ascension.

The Fuggers became so well known around Europe that they had to change the spelling of their name from…you guessed it.

The New Emperor of Germany

Hugo Stinnes understood Cantillon Effects better than anyone. He used the Weimar hyperinflation to become so rich that Time Magazine called him “The New Emperor of Germany.” Which was mighty awkward after World War I.

Stinnes’ strategy was simple. He borrowed as much money as he could and bought businesses selling real resources like coal. As the money became worthless due to hyperinflation, his debts evaporated. He was left owning the immensely valuable resources and businesses that he’d effectively bought for almost nothing.

Stinnes’ empire grew absurdly large. But he forgot Cantillon’s most important lesson. Bubbles driven by credit eventually burst.

Currency reform completely crushed Stinnes’ empire after he died.

Satoshi Nakamoto

The creator of Bitcoin launched the cryptocurrency in 2009 to usurp the fiat money system. Bitcoin is supposed to be a superior form of money. Instead of trusting in central bankers and the banking system, people should trust maths, cryptography, distributed ledgers and blockchain.

The popularity of Bitcoin led to its own demise as money. As the price has hurtled higher, its value as money has fallen. Bitcoiners now hold onto their bitcoin instead of using it to escape fiat money and the banking system.

Nakamoto’s Bitcoin stake is now worth about £100 billion. Not a bad reward for launching a currency revolution…

Soros broke more than the Bank of England

Floating exchange rates are considered perfectly normal these days. Indeed, most people probably don’t even remember the age of fixed exchange rates.

But George Soros made his fortune on the revolution in money as the world transitioned from fixed to floating rates.

The most famous episode was when Soros “broke the Bank of England”. He bet the Bank couldn’t maintain the pound’s currency peg. And he was right.

But Soros played much the same game years before in Southeast Asia. It made him even less popular there.

The point is that Soros understood economics and the nature of money. He knew a revolution was coming. And bet on it.

The latest revolution in money

If your own family didn’t make the list, I’m sorry to have missed you.

But your opportunity to make a start on appearing in next year’s edition is now approaching.

A revolution in the nature of money is once again upon us. It is already playing out in the Global South. Developing nations are leading the charge.

Soon, it will capture all of us. And that should trigger spectacular gains in one small sector of markets.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Editor at Large