- Fiscal management is an art form, not a science

- Is it too late for taxpayers to bail out the Treasury?

- Gold deserves our trust, not politicians

The trouble with fiscal delusions is that they can last dangerously long. By the time a Chancellor realises they’re wrong, they’ve long since retired. On a snazzy pension, of course.

Right now, the debate about the budget is suffering from all sorts of misunderstandings. Political careers rest on sustaining these delusions. Investors’ returns rely on untangling them before getting caught in the morass.

So, let’s take a closer look…

Are we going bust?

When you applied for a mortgage, did you submit the national GDP as your household income?

Of course not.

You have no claim on the national GDP as your own personal income, do you?

Can you imagine what your banker would’ve said if you wrote £2 trillion into the “income” box? It’d be ludicrous.

So why do we use national GDP when considering whether our government debt is affordable?

The government has no more claim on the entire country’s economic output than you do…

It’d require tax rates of 100%. But, as Rachel Reeves is discovering, tax revenue is not a knob you can dial up and down. Taxpayers are fickle things. Tax them too much and they play dead. Which only makes the national debt look even worse.

To calculate whether a debt is affordable, we can’t use national GDP as our income figure. We must use actual income. For you and me, that’s our pay. For the government, it’s tax revenue.

When a bank assesses our borrowing capacity, it uses a debt-to-income ratio. Our borrowing divided by our pay. The rule of thumb is that a bank will lend about five times your income.

Of course, no bank would lend to someone whose outgoings have been larger than their income for 24 years straight…

Certainly not without any collateral, which is how governments borrow.

But the analogy remains useful…

When we ponder whether our national debt is affordable, the correct ratio to use is government debt divided by tax revenue. The government’s borrowings divided by the government’s income.

The UK’s debt-to-income ratio stands around 2.6. Meaning the government owes 2.6 times its annual tax take. That’s about middle of the pack for the 10 largest economies.

Unfortunately, the data is actually a bit sketchy and not very comparable between countries. There are too many variables.

For example, in many countries, debts and taxes are distributed between national and state governments in rather odd ways.

If that topic interests you, be sure to take a look at how Australia attributes its taxing and spending between the Federal and state governments. It’s a real laugh.

In Japan, you can choose to redirect some of your local tax payment to another city and get a gift in return!

The point is that the data is iffy. In fact, economists use debt-to-GDP ratios because the data is accurate and comparable, not because it makes logical sense.

Only an economist who believes in 100% tax rates should be allowed to use the debt-to-GDP ratio though.

Anyway, in terms of our debt to revenue ratio, we’re not shot yet.

The price of debt

Another consideration for the bank is whether you can afford the repayments on a month-to-month basis. For household debt, affordability metrics often require debt payments to be no more than a third of income.

Again, economists like to use the wrong figure. They calculate the interest cost as a share of GDP or government spending. But it’s interest cost as a share of tax revenue that matters.

But that metric doesn’t really work for governments either. Their debt is like an interest only loan. They don’t repay the debt over 30 or even a thousand years. They just keep borrowing more.

Still, debt interest has fluctuated around 8% of tax revenue since the GFC. That hardly sounds oppressive. Most mortgaged households would love to pay that share.

It’s also largely money paid to our own pension funds, insurance companies and banks. All of whom pay taxes – a bizarre merry-go-round.

And any payments to foreigners are largely offset by our own pensions’ investments in foreign debt.

It’s also important to remember that tax revenue tends to grow quite fast even without hikes. Inflation alone is a major tailwind that both gooses tax revenue and devalues past debts.

So far so good. We can afford our debt. But there are some reasons why even these metrics don’t work…

Government debt is not the same as household debt

One crucial difference between household and government debt is that, when taxpayers borrow, we tend to invest the money in an asset. Usually, one that helps us earn income or save money. A home buyer no longer needs to pay rent, for example.

The government, however, borrows to spend on consumption. Welfare, defence and all sorts of other outlays are spent, not invested. It’s more like a credit card than a mortgage.

Debt is only a good idea when it is productive. If it doesn’t help produce future income, it’s downright dangerous over time. Because the debt begins to detract from your spending.

Most important of all is that this time really is different. Demographic pyramids have never been shaped like this before. For the entire history of civilisations, government debt was always a self-solving problem. You just had to wait for more shoulders to come along and bear the burden, by right of birth.

That won’t happen anymore. We’re in for a shrinking cohort of taxpayers who are expected to bail out the government.

If I’m confusing you with all this, you’ve grasped the point of this article entirely. Fiscal management is more of an art than a science. It’s a different kettle of fish from anything else. A whole new ball game you’re expected to play without knowing the rules each time you vote.

Voters and therefore the chancellors they elect can hardly be expected to get it right the first time… But politicians rarely make comebacks to fix their own mess.

A very different perspective

Instead of trying to understand the art of fiscal management, consider the alternatives we must choose from. Compare the recent speeches of Nigel Farage and Chancellor Rachel Reeves.

Nigel is openly predicting a fiscal crisis in 2027, which forces the government into austerity. Proper austerity, this time.

He says that Labour’s MPs will refuse to back this, triggering an election.

You’ll never guess who wins.

What makes this interesting is that a Reform UK government installed during a debt crisis is likely to follow very different policy from what’s promised…

If Nigel is right about the coming crisis, the election campaign is going to look very different to what’s going on now. And the Conservatives are actually a good bet.

But predicting a fiscal crisis is an astonishing thing for a politician to say. It also explains why Reform seem to be in election mode when it comes to policy.

Our chancellor, meanwhile, is breaking election promises because she is surprised by the state of the economy she is running…

This is an extraordinary combination. Not only doesn’t she know where she is going, she doesn’t know where we came from and claims someone else is steering the ship. She’s only there to rearrange the deck chairs.

This is especially poignant for me personally because I didn’t follow Nigel Farage’s politics very closely, but I listened to all of his speeches anticipating what would go wrong for the euro and how the European Sovereign Debt Crisis would unfold.

And he was consistently right.

Now, he’s applying the same arguments and predictions to the UK’s own fiscal crisis…

The great escape

One day, Nigel will get more credit for his campaign to keep us out of the euro than the EU. Because it matters far more. Last decade would’ve looked radically different without the pound and the Bank of England in charge.

But if Nigel is right about 2027, things will be fascinating. It may even give him the economic credentials to impose proper austerity.

For now, though, it remains far more likely that governments will follow the traditional approach to dealing with too much debt. They’ll turn to the central bank for financing.

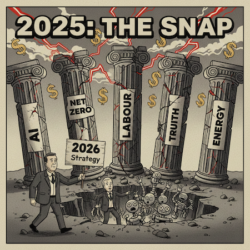

That’s why the gold price is surging. We are approaching crunch time. It’s difficult to say where the knockout blow will come from. But the national finances are on the ropes. Something has to happen.

Government bonds are transitioning from a safe haven to a risky asset. The risk comes in the form of inflation, not default, of course.

And gold is the easiest way to escape.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Editor at Large