- Nationalise the pension system

- Default on government bonds

- Inflate away the debt

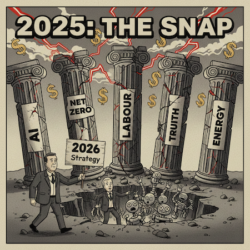

Don’t worry, Rachel Reeves hasn’t been arrested and put in the Fleet. It’s the entire country that’s stuck in debtor’s prison.

On Tuesday, we examined how the UK ended up here in the first place. Today, it’s time to ponder how the Chancellor will try to get us back out.

By the way, it doesn’t really matter who the chancellor will be. In fact, it’ll have to be the right mix of characters. Because this’ll take about a decade.

That’s according to the IMF study which examined how countries “liquidate” their debt once they land in debtor’s prison.

The IMF’s plan was written to help the likes of Greece. But thanks to COVID policies, it now applies to many more countries.

There are three ways for a country to escape debtor’s prison. But I think we’re in such a deep dank cell, it’s going to take all three of them to get us out.

So, it’s worth knowing about and understanding all three, if you want to survive with your investment capital intact…

1. Inflation spikes will continue

Back in 2020, as the government’s response to the pandemic began, I predicted a wave of inflation.

Unlike people who’ve been crying wolf about inflation since 2008, I said the inflationary wave was coming for a rather odd reason: the Bank of England wanted it and the government needed it. The inflationary spike was a deliberate policy choice. It would be “How you will pay off Britain’s Covid-19 debt,” I wrote.

Have you noticed that your mortgage appears bizarrely small to you decades after you signed on the dotted line? Or how the Napoleonic War only cost £1.65 billion? It’s because inflation devalued those debts over time too.

The basic idea is simple. Governments can devalue their debt by deliberately causing inflation. That’s because the economy grows with inflation, but debt does not.

Of course, this is fake growth. It doesn’t make us wealthier in real terms. But it does make past debts worth less relative to the size of the economy. The debt to GDP ratio goes down.

This worked spectacularly well for countries like Greece and Spain in 2022. Their debt to GDP ratios were crushed by the inflationary wave.

Only the UK was dumb enough to issue a large pile of inflation linked bonds. Their cost surged with inflation, negating much of the beneficial effect.

Anyway, the 2022 inflation spike was a deliberate policy of governments to cut their debt burden. This explains why they were so slow to wake up to spiking inflation rates. They wanted them to spike.

But debt remains a problem. According to the IMF document which explained to governments how to use inflation as a “liquidation tax,” it works best over long periods of time. We are in for a series of inflationary spikes. At least, that’s what governments and central banks will try to achieve.

The key for this policy to work is to keep inflation above government bond yields. Which makes those investments notably bad. And this one notably good.

It also means that government bond yields must tumble soon, or inflation must spike again.

2. Defaults, in all their kinds

A UK default on government debt may seem unimaginable. But countries like Greece and Argentina did default on their debts. It can be done as part of a manageable process that doesn’t trigger a crisis. That is the allure of an IMF program. It triggers the possibility to negotiate with bond holders.

For example, lenders to the government might be pressured to take a haircut on the yields their bonds pay. Or institutions might be forced to invest in government bonds as part of their regulatory oversight. After all, the government bailed out many of them in the past. You can’t have government deposit insurance without financing your government…

Defaults of a sort can also occur via spending and tax promises…

I expect the government to nationalise the pension system, including ISAs and SIPPs. They will replace it with a means-tested state pension.

The government bonds investors hold in their pension pots will be written off as part of the plan. That’ll amount to a default too. But, because you’ll receive a state pension plan in return, they won’t call it a default at all. It’ll be an asset swap. With all sorts of supposed benefits and improvements.

If you have your doubts about this, you may want to check out investments that are outside the government’s grasp.

The more important default is on spending promises.

3. Austerity is coming back

We all understood why the likes of Greece needed to cut government spending dramatically in 2010. It took about five years for government policy to get there.

Well, the UK will be back in the austerity box soon. At least, that’s what the critics will call it. The rest of us will see it as common sense that a government must live within its means.

But the point is that we have reached the end of the line on how much creditors will lend. Those still buying UK government bonds are essentially punting on the prospect that the government will eventually be forced to cut spending spectacularly. That a vast turnaround and austerity program is coming.

One intriguing aspect of this is that it doesn’t matter who is in government, what their ideology is, or what they promise during the election. When the money runs out, you have to cut. It’s a simple matter of maths.

To learn about how this clash eventuates, check out books about negotiations between the Troika and Greek Finance Minister Yannis Varoufakis. It genuinely makes for great reading.

According to a book by a pair of Bloomberg journalists, the Greeks came armed with theory and research, ready to debate. The Troika listened politely and then simply crunched the numbers on what level of spending Greece could actually afford. And then told the Finance Minister to implement it.

He resigned. But they found someone to replace him, ignore a referendum and fire up a chainsaw.

That moment is coming for the UK. It usually requires the IMF to set up shop in order for the government to have someone to blame for the cuts.

The UK bond market’s wobbles reflect growing doubt that the turnaround is coming at all. At this point, only the central bank’s backing and regulatory demands to hold gilts are keeping investors in the market. But they won’t stay if inflation comes back too strong.

That’s why I see the future as a bizarre three directional pendulum between austerity, default and inflation. Inflation to devalue the debt and defaults to cut its cost. And spending cuts because the government will have to begin living within its means at some point.

Now what?

I’m quite confident in these predictions. Although the proclivities of politics make the timing difficult to anticipate.

The gold market is already warning you of what’s to come. The bond market is getting antsy. But the pound remains astonishingly strong relative to so many currencies.

If it plunges, these four investments will outperform strongly.

To be honest, the real challenge is going to be finding a chancellor willing to do what it takes. They can’t even cut immigration. How are they going to nationalise the pension system?

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Editor at Large

P.S. I’ll admit it — what we’re sharing with you next is different. It’s not another tech rally, crypto play, or a high-risk trade. It’s a brand-new income strategy from Sean Allison that focuses on generating consistent cash flow from real, established companies — without needing to buy a single share upfront. It’s simple, repeatable, and designed for everyday investors who want the chance to generate income they can actually use. We’re putting the final touches on the release now…and you’ll be among the first to see it. Keep an eye on your inbox — full details coming very soon.