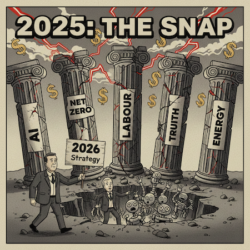

In today’s issue:

- A transformer failure caused massive disruption at Heathrow, highlighting a global shortage of ageing, overstretched grid infrastructure

- Transformer prices have surged up to 100% since 2020, with tariffs and AI-driven demand set to intensify supply bottlenecks

- Investors can benefit from rising demand through global transformer manufacturers

On 21 March 2025, chaos struck Heathrow Airport.

A fire at the North Hyde electrical substation in Hayes knocked out power to key systems, dimming terminals and bringing operations to a halt.

The result: approximately 1,300 flights were cancelled or rerouted, and nearly 300,000 passengers were stranded worldwide. Airlines faced a staggering bill, with losses estimated between $50 million and $100 million due to rerouting, passenger accommodations and other associated costs.

The cause wasn’t a cyber-attack or a fuel shortage – but a failure in a critical power transformer.

Power was eventually rerouted and Heathrow resumed operations. But for infrastructure experts and investors, the incident wasn’t just a one-off – it was a symptom of a much deeper problem. The global supply of power transformers is dangerously strained.

Power transformers are the unsung heroes of the grid. They step voltage up or down to allow electricity to be transmitted safely across long distances. Without them, energy from a wind farm can’t get to a city, and the power to run an airport can’t be safely distributed.

But today, the world is facing a quiet but critical transformer shortage. As Bloomberg recently reported, the lead time for a new transformer has ballooned from months to over two years in some cases.

Prices have surged too – transformers now cost between 70% and 100% more than they did in 2020.

This is due to a convergence of factors. Transformers rely on high-grade electrical steel and copper, both of which are in tight supply and dominated by a few global producers.

In the US and Europe, many transformers are more than 40 years old – far beyond their intended lifespan. Manufacturing transformers remains a labour-intensive process, often requiring skilled hand assembly, and those skills are increasingly scarce.

Meanwhile, the global push to decarbonise – through EVs, renewables and widespread electrification – is putting enormous strain on an already overstretched grid. All of this infrastructure runs through transformers.

But to make matters more complex, transformers are also extremely vulnerable to trade disruptions, with the US, in particular, importing 70-80% of its largest transformers. In fact, US imports of transformers rose to 4,270 units in 2024 – more than 3.5 times the trailing ten-year average. But about half of those imports come from Mexico, which has become the main supplier of large power transformers to the US market.

Certainly, if new tariffs are imposed on Mexico, as US President Donald Trump and others have proposed, the result could be even more severe shortages – and even higher prices.

Such policies would likely worsen grid bottlenecks just as AI data centres and electrification drive electricity demand higher. Korean, European and Brazilian manufacturers could be among the biggest winners, as US utilities and grid operators scramble to diversify away from North American suppliers.

Some manufacturers are already expanding capacity within the US, but this buildout is unlikely to be completed before 2026. In the meantime, any broad-based tariffs on Mexico (and, to a lesser extent, on Canada) could act as an unintentional subsidy to non-North American producers with ready capacity to deliver large-scale transformers.

Of course, you might not be surprised to read that the transformer industry is now highly competitive. Leading players such as Hitachi Energy, Siemens, GE and Schneider are capital goods giants capable of offering end-to-end integrated energy solutions.

But they now face increasing competition from a growing number of Chinese entrants. This intensifying rivalry may lead to further consolidation in the years ahead, especially as smaller firms struggle to keep up with demand and compliance requirements.

For investors, this bottleneck is more than a warning – it’s an opportunity. Transformer manufacturers are emerging as critical infrastructure players. Companies like those mentioned above are now in a position to command higher margins and longer-term contracts as governments and utilities scramble to secure supply.

There are also opportunities further down the supply chain. The transition to clean energy won’t happen without transformers, and that spells growing demand for the raw materials and components that go into them – such as copper windings, insulating oils and electrical steel. Mid-cap companies with exposure to these inputs are likely to see sustained tailwinds.

Even here in the UK, investors can gain exposure. For example, TT Electronics (TTG) designs and manufactures specialised electronic components for power infrastructure and industrial applications. With rising demand for grid reliability and custom energy systems, firms like TT Electronics are well positioned to benefit.

Meanwhile, the long investment cycle in grid modernisation is just getting started. Governments around the world are pouring billions into grid upgrades. This is not a cyclical opportunity, but a structural one that could play out over decades.

No wonder private equity and infrastructure investors are already circling. The predictable demand profile, long order books and strategic importance of transformer makers make them attractive takeover targets. And the threat of future blackouts – not just at airports, but at hospitals, data centres and industrial hubs – will only intensify the urgency.

Investors often chase the shiny edge of innovation – AI chips, electric vehicles, biotech breakthroughs. But sometimes the best returns come from backing the boring but essential.

Transformers don’t trend on Twitter. But they’re the invisible backbone of the modern economy. Heathrow’s 21 March blackout was a wake-up call – and for the smart investor, it could also be a signal.

Until next time,

James Allen

Contributing Editor, Fortune & Freedom