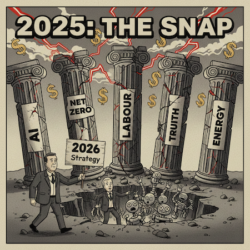

- Renewables are poisoning our grid

- Equipment replacements during a shortage?

- Which commodities does a grid need?

Back in 2023, London Mayor Sadiq Khan admitted something astonishing. Transport for London raids the London Transport Museum to repair its trains.

It’s good for a laugh. And tells you lots about the state of the UK.

But what if the museum didn’t have the goods?

I’m worried that’s what’s about to happen to our electricity grid…

You probably know about the current backlog in electricity production, transmission and distribution equipment. We don’t have the workforce, the factories or the energy needed to make the grid infrastructure we need. And the countries that do have the capacity are booked out for years.

The wait time for the gas turbines that produce electricity is about three years. Some transformers have a lead time of four years. Power plants are having to wait years to connect to the grid. And new transmission infrastructure delays keep blowing out, too.

All that is already well known and understood. Its impact on our ability to roll out the grid we need is currently undermining all sorts of projects. Not to mention spiking power prices.

We predicted this mess back in 2024 when it became clear we’d committed to a renewables-based electricity grid, “but forgot to build” one capable of actually handling renewables.

Oops.

But here’s the realisation that’s going to hammer home next…

The price of stability

What caused the blackout in Spain is almost irrelevant. Electricity grids get hit by all sorts of disruptions. A lightning strike, for example, caused a blackout across parts of England, Wales and Scotland in 2019.

Of course, renewables are more vulnerable to such things. That’s true for a long list of reasons.

The obvious example is weather causing supply disruption. In 2019, a cloud caused a blackout in Alice Springs, Australia. But coal plants can fail unexpectedly too.

Another source of instability is the size of the transmission and distribution system. It must be vastly larger for a grid that uses a lot of renewables because they tend to be located in remote places. And they produce intermittent power that must be moved around greater distances to provide more reliable supply.

But all this shouldn’t necessarily matter. Because it is the robustness of the grid to such shocks that is the key. How big a punch on the nose does it take to cause a blackout? And what’s the cost of reducing this risk?

You can’t eliminate it. The real question is how much money you have to spend to reduce the risk to the level you’re willing to live with.

Renewables spike that cost. Because they introduce supply instability. But that’s not the point I want to focus on here.

Renewables produce electric poison

Renewables dramatically increase the level of voltage and frequency fluctuations on the grid. These actively damage electric equipment. Equipment that uses electricity, provides it and keeps it stable.

The blackout in Spain was so large and cascaded so fast because the voltage fluctuations caused power stations to disconnect. They did this to protect themselves from the chaos of the grid.

Dirty power, as engineers call it, is dangerous. Electric equipment is designed to disconnect itself rather than bear the brunt. So, if you increase the amount of dirty power on the grid, you raise the risk of such disconnections.

Spain was an extreme example. But what investors need to realise is that these fluctuations are happening on a smaller scale more and more frequently. The fluctuations may not be enough to cause disconnections that cascade into an international blackout each time. But, like a poison, they are gradually destroying our grid.

Bloomberg has the figures on how often these disruptions are happening:

It’s not just Spain, surges in voltage are happening more often in Europe with the rapid addition of renewable power generation. In 2024 there were a record 8,645 instances when voltage rose above allowed European limits. That’s more than a 2,000% increase from 2015, when there were 34 alerts, according to data published by the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity, known as Entso-e. That’s like getting an alert almost every hour, up from fewer than three times a month a decade ago.

That’s just voltage. Frequency divergences are an even bigger problem. Including on the distribution system, where they are rarely measured.

And those measures only consider fluctuations outside of regulatory limits. Fluctuations within the guidelines are also happening. And they matter because they wear out the equipment that makes the system work.

In March, a transformer failure caused a blackout at Heathrow. What I’m trying to tell you is that such failures are going to become commonplace because renewables are poisoning our grid with unstable voltage and frequency. They are damaging the equipment that keeps things working.

Now, combine this topic with the existing backlog of new transformers and other electrical equipment…

Do you see where I’m going?

Replacement parts during a shortage?

Our grid’s components are about to experience a growing rate of failure at a time when we are already struggling to provide the parts we need to expand the grid. If failure rates become more common, the entire grid is increasingly at risk of becoming unfixable within reasonable timeframes. We simply won’t have the goods.

If Transport for London had been unable to raid the Transport Museum for replacement parts to repair the Bakerloo Line, what do you think would’ve happened to the rest of London’s public transport system?

It would’ve been gridlock.

And that’s how Spain’s blackout spread.

Ramping up manufacturing of electrical infrastructure gear is hard to do. Companies like GE Vernova are reluctant to invest when demand is fluctuating heavily. Demand for gas turbines went from a total of 1 in 2022 to a backlog of years in 2025, for example. Besides, we were supposed to phase out gas turbines, not build more!

If the grid starts to fail, we are looking at a sustained period of chaos that’ll be hard to fix. And repairs will mean leaving new projects with further delays.

Grid chaos has barely begun. As even Bloomberg is now publishing, “Spain is not going to be the last blackout to happen.”

How to profit?

In this week’s Fleet Street Letter update, my colleague Down Under reveals a number of Australian companies that are positioning to profit from the vast grid upgrades the country needs to keep its grid stable. Unlike other governments, the Australians can still afford to spend a few hundred billion on their power systems.

Personally, I prefer to bet on their failure. Spain and Germany are stepping up their use of gas power to make up for renewables’ shortcomings, for example. If we wake up to the damage renewables are doing, and the backup gas system becomes the baseload power supply instead, that implies vastly more gas demand.

Or renewables could be required to provide stable and green power by linking to batteries to clean their power.

Another option is to speculate on the commodities that’ll be in demand as the world tries to rescue its grids. Copper is a good example. But this one is even better.

However, you try to adjust your portfolio, now is the time to do it. The risk of blackouts is soaring.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Editor at Large

P.S. I’ve just shared the details of what I believe is the best way to position for this — the single commodity I expect to surge as the world scrambles to repair its failing grids. You can see my full analysis here.