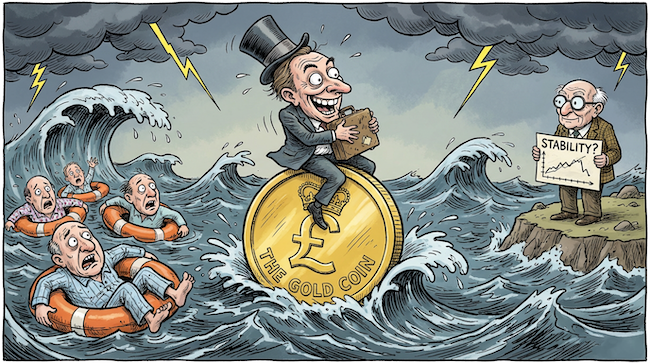

- Why commodity prices are so chaotic

- Volatility works both ways

- What goes up fast comes down fast too

Financial markets were extraordinarily volatile last week. Especially the commodity markets we focus on in Investor’s Daily.

Precious metals prices plummeted. And energy markets whipsawed on bad weather and geopolitics.

The chaos is disconcerting. But does it really matter?

If you had gone into hibernation two weeks ago, the value of your gold would be the same when you woke up today.

Yet gold investors have barely slept for two weeks as the price soared and then plunged…

Today, I want to give you a scientific way to think about risk. Because it may change how you think about markets during volatile times like this.

It might just help you sleep better too.

Risk isn’t bad

One of the strangest concepts in finance is that risk is directionally agnostic.

Risk is not defined as “the chance of something going wrong.” Nor is it “the probability of the price falling.”

In finance, whether a price goes up or down is irrelevant to how risk is measured.

Instead, risk is defined by the speed and magnitude of a price’s move in either direction. We call this volatility. It is measured by the size and frequency of historical price moves.

When prices are jumping and plunging, volatility is high. And so the asset is considered high risk.

I know that’s confusing, at first. We usually think of risk as the likelihood a stock’s price will fall.

Investing in small companies isn’t “higher risk” because they’re likely to crash. It’s “higher risk” because they move further and faster – both up and down – than blue-chip stocks. The risk cuts both ways.

Thinking about risk as volatility makes intuitive sense if you look outside the stock market.

Most financial markets are a zero-sum game. One person’s gain is another one’s loss. Each position has a counterparty betting the other way.

For example, if the pound plunges against the US dollar, that’s not “bad” as such. It just depends which way you were positioned.

So “risk” can’t be defined by whether prices are rising or falling. A falling price is good news for someone positioned the right way.

Therefore, a scientific measure for risk can’t be dependent on the direction of the move. Instead, it is a measure of how far and fast the price has been moving about lately.

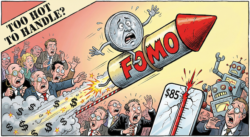

Volatility is the source of an investor’s profit

It might seem dodgy for financial markets to be a zero-sum game. What’s the point if all the gains and losses net out?

Their purpose is to transfer risk from those who don’t want to take it to those willing to bear it.. This is incredibly valuable to the economy overall.

It’s a bit like insurance. You don’t pay your premiums expecting to make a profit . You pay them for stability.

Let’s take wine futures as an example.

Before wine futures existed, a bad harvest could send a winery bust. A frost could wipe out a family business going back generations.

Wine futures allowed speculators to bear this risk instead. Under a wine futures contract, a merchant gets a fixed price for the wine before the grapes have even been harvested.

In a good year, futures buyers make out like bandits because they paid a low price for great wine. In a bad year, they overpay for inferior wine and take the loss.

The winery gets the same steady price each year – and it gets paid in advance, which finances operations.

The financial stability allowed wineries to improve their product over time. Many of today’s most valuable wines come from wineries that have a history of using futures. They rarely went bust. The knowledge of making wine got passed on in a stable way.

That shows how transferring risk can improve economic stability and growth. Financial markets move risk around from those who want stability to those willing to take it on.

But the merchants only take on this risk in exchange for an expected return. They buy the wine futures at slightly lower prices than the wine’s expected value. Over the years, this nets out as a profitable business.

The uncertainty in the wine’s value is their source of profit.

The more unpredictable the wine’s value, the greater discount the merchants demand in the futures market to ensure they make money. In that sense, volatility measures expected profit – not just risk.

Higher volatility implies higher expected returns. That’s why risk and reward go together in financial markets.

Risk, for lack of a better word, is good

Last week we saw many commodity prices plunge and soar. Volatility overall rose.

Crucially, it rose before the plunge.

Volatility was already elevated when gold and silver took off at extraordinary speed in the weeks prior.

My point is that investors who understand “risk” as “volatility” would not have been surprised by the sudden correction. Volatility rose before prices fell so far so fast. Risk was high.

In an environment with high volatility, you need to expect both large gains and losses to occur.

The key takeaway is that both occur. We can’t invest for large gains without experiencing large corrections along the way.

But those corrections are merely a reminder that we are indeed targeting large gains in the first place.

Volatility works both ways.

As long as you understand that going into the trade, it shouldn’t force you out when it temporarily moves against you.

We are back to where we were two weeks ago. But volatility remains high. That implies more gains could be on the table.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Editor at Large, Investor’s Daily

PS My point is, volatility isn’t the enemy. It’s the source of opportunity. While most investors panic during gold’s wild swings, a handful of billionaires are positioning differently — using a lesser-known gold strategy designed to thrive in chaotic markets. If you want to see what Richard Branson is doing instead of simply “holding gold,” you can learn more here.