You have £1,000 sitting in the bank.

You have £1,000 sitting in the bank.

You want to invest all of it in a stock.

You have a YOLO (you only live once) mindset because you’re comfortable with risk.

You spot a stock you like.

The stock price is on a strong up trend.

After a tip off from a mate, you’re convinced the price will continue to rise.

Easy money…you hope.

You put £1,000 into “Company X”.

Then, you wait.

What are the emotions in play here?

Greed? Excitement? Fear of missing out (FOMO)? All of the above?

At first, it works. The stock pushes higher and you’re thrilled. This “sure thing” looks like a winner.

Until it doesn’t.

The price crashes 20% in a single day. Then another 7.5% the next. Earnings disappoint and the market reacts fast.

Suddenly you’re sitting on a loss. The hopium evaporates. Panic takes over.

Now comes the hardest decision. Do you cut your losses? Or do you wait for a turnaround?

Things could get worse. They could also get better.

You’re stressed. Confused. Tired of this whole investing game.

You eventually decide to cut your losses. You can’t stomach the fear of losing even more money.

However, a couple of weeks later, the company’s stock price heads higher than what you got in at. Maybe you should get back in, have another go at it…?

**palm to face moment**

Buy high sell low

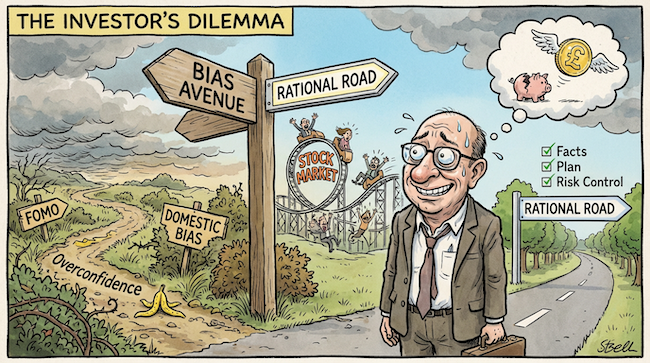

This is an all-too-common example of investing without understanding the impact of behavioural finance and bias.

Understanding how behaviours and biases affect your investing is a huge part of figuring out where to put your money.

Often, when people make investment decisions, they act on biases that heavily influence decision-making.

Some of these biases might be overconfidence, confirmation bias, framing bias, anchoring bias and domestic bias.

Take domestic bias, for instance. It’s widely known in the investment world that retail investors typically prefer to invest mainly in their domestic stock markets.

That “close to home” bias — favouring a familiar market — often limits the selection pool to what’s available locally, in our case the London stock market.

A couple of decades ago, that made a little more sense because it was harder to invest in overseas markets.

But in today’s world of app-based and online brokers, accessing the markets in the US for example is as easy as investing locally.

In fact, I’d argue the US markets aren’t really “US markets” anymore. They’re as global as any market you’ll find.

The browser you’re reading this in — is it Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, or Apple Safari?

OpenAI and ChatGPT are American. Gemini from Google is American. Claude from Anthropic is American. Grok from xAI is American. Copilot from Microsoft is American.

So why would you only consider stocks in the UK?

You can easily see whether you suffer from domestic bias. Just look at your portfolio. How many stocks are listed on the London Stock Exchange, AIM or Aquis Exchange? How many are in the U.S., Canada, Australia, Europe or Asia?

The point is this: recognising domestic bias and opening up your investment world from domestic to global gives you a far better shot at successful investment outcomes because you can invest where the action is, not where you hope it should be.

Three ways you can use behavioural finance to invest

To combat bias and reduce the impact of behavioural finance, I believe there are three steps you can take.

First, only risk money that you can truly afford to lose.

This prevents you from getting emotionally attached to the money, making it easier for you to ride out any volatility.

You can manage rationally far more effectively when less is riding on the outcome.

Imagine losing £5 overnight from a £10 investment. Not ideal, but manageable.

Now imagine £100,000 turning into £50,000. Same percentage loss. Completely different emotional response.

I’ll share more on risk soon — it’ll be worth reading — but you get the idea.

Capital allocations and risk management are ways in which you can control your behaviour in the market that might force you to act irrationally.

Investing is hard enough as it is, so you don’t need your emotions to make it even tougher for you.

Second, set realistic expectations and goals with a strategic plan.

You’re never going to be able to perfectly time the market.

So don’t try.

If your entry into a position is bad timing, then time-frame is your friend.

If you want to invest for the long term, then invest for the long term. Find the stocks you want to hold for 10, 20, 30 years, assess your capital allocations and set the plan in motion.

Don’t expect every stock to win. Some will lose. Some will underperform. Some will exceed expectations. Nothing will go perfectly to plan. So don’t expect it will.

With realistic expectations and a clear plan, you always have a reference point to return to when emotions run hot.

Dollar-cost averaging can also help smooth volatility and remove the pressure to time the market. In other words, invest a fixed dollar amount at regular intervals regardless of share price. Build it into your strategy and you eliminate much of the stress around market swings.

By not trying to be perfect, and being realistic, you can remove a lot of the behaviours that get investors into so much trouble.

Third, prioritise facts over personal biases. In the long run facts beat perceptions, hands down.

Given weak macro conditions or poor fundamentals — revenue, profits, contracts, pipeline — is a stock really likely to rise just because your mate from the pub thinks it will?

Probably not.

Ask yourself: what does the data suggest?

Look at things like the market size, the competitors in an industry, the unique aspects of the company you want to invest in. Consider whether it plays a critical role in future supply chains, or whether current deals could unlock significant future revenue.

Then ask how those goals get funded. Do they have cash? Are they profitable? Can they become profitable? Have they hit past milestones? Is deal flow consistent? Is institutional money showing interest?

Investing is not an exact science, and the market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.

This is a game of educated probabilities, but you need to also consider the evidence over personal biases or “feelings” to give yourself the best chance.

Also, just recognising that behaviours and biases are important is a big step towards success.

By recognising its influence and impact you’re already a step ahead of most investors.

And in markets this wild, every advantage you have at your disposal makes a difference.

Sam Volkering

Contributing Editor, Investor’s Daily

P.S. One of the most expensive biases in investing is availability bias — over-focusing on what’s loud, familiar, or already obvious… while missing what’s quietly actionable.

Right now, everyone knows SpaceX is coming. The headlines are shouting about a $1.5 trillion IPO. But most investors stop there and assume they’ve “missed it.”

That assumption is exactly the bias that costs people money.

There’s a way to gain exposure before the IPO, using something that already trades today, inside a normal brokerage account, with a relatively small amount of capital. No private deals. No hype chasing. Just positioning early, before the crowd connects the dots.

If you want to see how this works — and why most investors overlook it — you can read the full breakdown here.