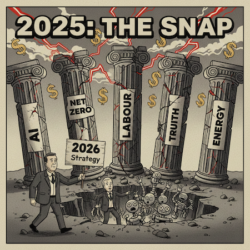

- Financial markets are about to turn topsy turvy, again

- Most investors have no recollection of normality anymore

- Politics is “through the looking glass” too

Nine years ago, my friend Tim Price was busy getting his book published. It’s matured like fine wine since. The title alone is worth the price of admission: Investing Through the Looking Glass: A rational guide to irrational financial markets.

I wonder if Tim thought irrational financial markets would last this long, though?

The basic idea of the book was that central banks and governments had turned the investment world upside down and inside out.

It now helps investors to think of impossible things before breakfast. Because they just keep happening!

Remember the “bad news is good news” mantra? It’s popped up a few times since Tim’s book. But the concept remained the same. Bad economic news allows central banks and governments to take action. And their loose fiscal and monetary policy is what bids up stocks.

Good news causes central banks and governments to withdraw their support for the stock market. So, it’s bad for investors.

Investors trying to navigate this reverse psychology needed to read Tim’s book as a guide.

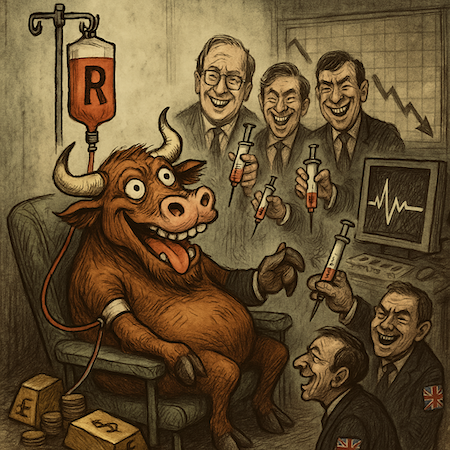

If that paradigm is back, investors hoping to get another high from the stock market need to pray for a recession to give them another shot in the arm.

There are a few problematic angles to all this, though…

What could possibly go wrong with irrational financial markets?

The big risk was always inflation. If central bankers or governments overdid the stimulus, then prices outside of the stock market would begin to rise too.

Critics claimed it was only a matter of time before governments or central banks would make a mistake. But it took a pandemic to be proven right.

For ten years, central banks and governments managed to walk the tightrope of inflation astonishingly well. They offset the deflationary effects of a moribund economy with inflationary policies. But didn’t overdose the patient.

The baton was gradually passed from governments to central banks over time. Because governments started going bust and couldn’t sustain the level of spending needed to keep the stock market alive.

Central bank stimulus is infinite. But even that flows mostly through the government bond market.

The point is, governments and central banks love a crisis. It puts them back in charge. They can look busy and use their policies to goose the metrics needed. Unleash welfare, force lending, bid up the stock market, bail out banks, hire public servants and countless other policies.

Suddenly, the political donors that politicians are used to begging from become dependents on the political system for their success.

What’s not to love?

A recession in the UK?

The warnings are growing louder. GDP growth in July was zero. More tax hikes and spending cuts are coming. Any cut to immigration would crunch GDP even more.

Worst of all, inflation remains stubbornly high in the UK compared to peers. That means the Bank of England can’t cut rates.

But notice how a recession would solve these problems?

Everyone’s a Keynesian during a recession. Even the OBR knows not to push the austerity button in an economic contraction. Not because of economic wisdom, but for fear of torches and pitchforks.

Even the Germans have now abandoned their debt break and fiscal frugality thanks to persistent recessions in recent years.

The point is, if you want to unleash spending during a time of fiscal quibbling, a recession is the excuse you were waiting for.

A recession is also likely to solve the Bank of England’s inflation problem. That’s because economists can’t tell the difference between inflation and rising prices.

There are all sorts of reasons why consumer prices might go up or down. Government counterfeiting is only one of them. And yet, central banks respond to every change in the price level as though it’s a monetary phenomenon.

If we’d had inflation targeting during the Industrial Revolution, we’d still be poor. Central bankers would’ve flooded the economy with money to stop prices from falling as factories tried to pass on the efficiency gains of mass production to consumers. But that’s a whole different story.

Today, we face a government dominated economy. And so a recession is seen as a political choice.

What happens next?

The day a recession is declared in the UK, everyone can heave a sigh of relief. Especially investors.

Another era of “bad news is good news” will begin for stocks. And with Labour in government, there will be no shortage of poor economic news.

The Bank of England will respond with rate cuts without waiting for inflation to drop. This’ll bail out the government and stimulate borrowing. That’s just what the economy needs, of course. More debt and more government!

We are now so far through the looking glass that we’ve forgotten what living in reality was like.

An entire professional cohort of financial market operators thinks this state of affairs is normal. And so they’ll cheer the intervention and feel relief that economic statistics provided sufficient justification for it. And stocks will soar.

Notice how the oldies are sounding like doom mongers these days. Respected leaders of large financial institutions warn about things like hyperinflation, civil war and the US government going bust.

The biggest punt investors must make today is to decide whether the world will come crashing down around them before or after inheritance taxes become their biggest problem.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Editor at Large

P.S. If a UK recession is the price for unlocking another round of monetary stimulus, rate cuts, and runaway stock gains… are you prepared to profit from it? One investor believes this looming downturn could mark the beginning of a “Wealth Window” — a rare shift that doesn’t wait for permission from headlines or economists. It rewards those who notice the pattern before the crowd. You can explore what he’s uncovered — and decide for yourself — right here.