- Why one sector of the stock market offers better odds

- “Resulting” is as dangerous to investors as gamblers

- Diversification done right

If I offered you seven-to-one odds on predicting the throw of a die, would you take it?

Presuming I don’t abscond with the money, the rational answer is yes. Because you have one in six odds of guessing correctly. So a higher payout is a favourable proposition.

But this is where things get interesting…

You have a five in six chance of picking the wrong number. So you are expecting to lose. Yet it is a rational decision to play anyway.

That means expecting to lose money can still be the right thing to do!

Say you take me up on the bet, but lose.

Was taking the bet still the right decision?

In hindsight, no.

But judging the decision by the outcome is what gamblers call “resulting.” You shouldn’t judge a decision by its outcome alone.

You should evaluate it based on whether you understood the odds correctly. And made the right decision given those odds.

Taking a seven to one bet on the roll of a die is rational. So the outcome isn’t what decides whether a decision was a good one or not.

How do we reconcile this?

Well, there’s a big difference between only playing the game once and playing it six or more times. If you play repeatedly, you can expect to win overall.

The answer is to only bet when you are allowed to repeat the game enough times for the odds to likely play out in your favour. This means only betting a small share of your money each time.

Now imagine I did abscond with the money you bet before the die was even cast. Then you really did make a bad decision. Because you failed to account for a real risk – counterparty risk.

The lesson? Understanding all the risks is crucial to making the right decision. Without it, you can’t know what the right decision may be. Even if you get lucky, you might’ve made the wrong decision.

Armed with these insights from a simple game, let’s apply them to investing…

What are the odds?

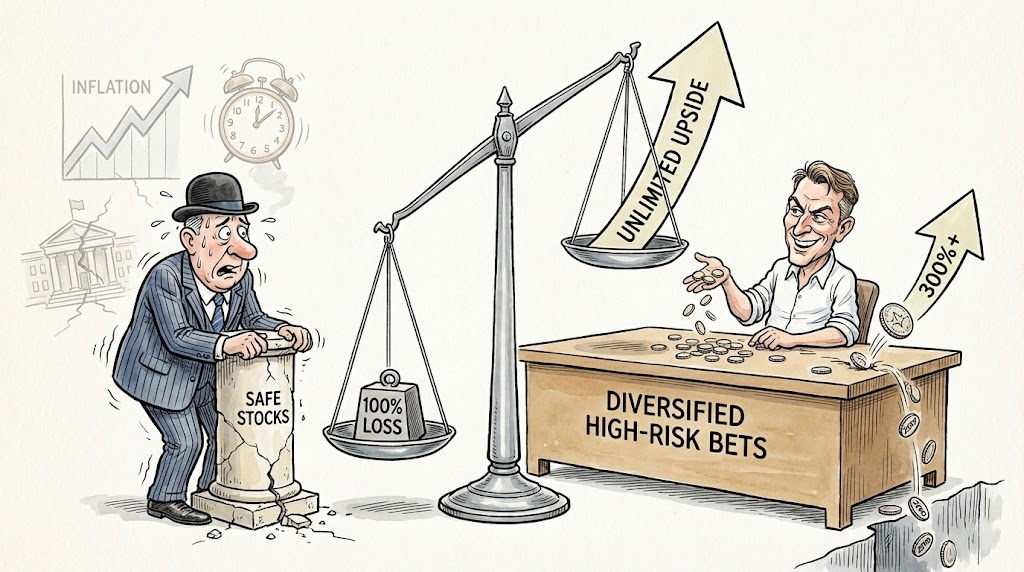

Share prices can go to zero. That’s the worst-case scenario. But how high can they go?

In theory, the answer is “infinity.” In practice, the point still holds.

The point is that stocks can rise more than 100%.

How is it relevant to today?

The answer lies in the payoff structure. It’s asymmetric. Meaning the size of potential gains is vastly higher than the maximum potential size of loss.

But that’s only true of stocks that have a high chance of doubling, at least.

If you make a punt that will either lose you money, or make you more than 100%, then the expected payoff is in your favour. You’ll gain more than you risk to lose.

Of course, the odds of gain or loss matter just as much as the relative payoff. And the possible outcomes are not this clear cut in the stock market. But we can still derive some important lessons from this.

Higher-risk stocks tend to offer more asymmetric returns. As long as the odds don’t move against you by too much, higher risk can be a better bet.

Investing in sectors with large upside potential can actually reduce overall risk simply because of the imbalance between a 100% loss and a greater than 100% gain.

Think about it like this. Given you are risking 100% of your money when you buy a stock, why not demand a chance of returns being greater than 100%?

As in our game, this proposition is only true if you can play it many times. So you also need diversification.

If you stake all your money on one such bet, you may get rich, or you may lose it all. The probability of a win won’t be much comfort if you lose, either.

But make 100 such bets and the odds begin to give you some more stability.

The last thing to consider is that we must do everything we can to tilt the odds of a win in our favour. That’s where traditional fundamental analysis of the company comes in. You need to avoid the duds, not identify the heroes.

If you can do all this, high risk stocks are a better investment.

Where might this high risk sector of the market lie?

Low-risk stocks can be deceptively dangerous

A stock that could double gives you asymmetric upside. Your possible gains are larger than your possible losses.

But what about boring stocks that probably won’t double? These don’t offer the same advantage.

Hopefully, they also put the odds of a gain in your favour. The chance of a blue-chip stock going to zero is certainly far lower than a high risk one.

But here’s the insight I want to show you.

All stocks suffer from risks that investors don’t often consider. Like the bookie absconding with your money after you place a bet.

Risks like inflation, a crash in the government bond market, management fraud, or technology making a product obsolete. Let’s call them external risks because they aren’t related to the company itself.

These risks tilt the board in favour of the stocks that are higher risk. That’s because these external risks play a proportionally smaller role in a high-risk stock’s success.

A blue-chip stock is waiting to be knocked off its perch by some bizarre crisis or development. It’s only a matter of time.

A high risk small company is so risky that economic or political surprises carry proportionally less weight in its success.

A 10% inflation rate will wipe out your expected returns from blue chip stocks. It has a much smaller impact if you’re investing in stocks that will either return more than 100% or go to zero.

Thus, high risk stocks allow you to diversify away many risks by making them proportionally less important to your overall performance.

Investors in thorium nuclear power or new drugs don’t care about inflation, for example. They have bigger things to worry about.

Where high risk strategies outperform

By sticking to high-risk stocks, you can take advantage of all the insights in this article.

You can make challenges like inflation or Labour budgets proportionally less important to your portfolio.

You can access asymmetric return profiles.

You can attempt to twist the odds of success in your favour by focusing on companies that you can understand.

You can use a high degree of diversification because you only need to invest a small proportion of your wealth in each stock to still get a chance of vast returns.

It sounds risky. That’s precisely why it works.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Editor at Large, Investor’s Daily