Publisher’s Note: British investors have been reminded more than once over the past few years that outcomes can change far faster than confidence does.

Publisher’s Note: British investors have been reminded more than once over the past few years that outcomes can change far faster than confidence does.

Markets lurch. Narratives flip. What felt like certainty six months ago suddenly looks reckless in hindsight. And too often, the damage is not caused by being wrong on direction, but by misunderstanding risk itself.

That’s why this piece matters.

It is not a story about getting rich quickly or losing money dramatically. It is a lesson in how people misjudge risk, especially after early success, and why experience, not intelligence, is usually what separates survival from disaster.

For UK investors navigating volatile equity markets, shifting interest-rate expectations, political uncertainty, and an increasingly global opportunity set, the distinction between risk and uncertainty is not academic. It is practical. It affects position sizing, timing, conviction, and most importantly, longevity.

This article reinforces a critical idea that professional investors learn the hard way: you will never have perfect information. Waiting for it is often the riskiest move of all. What matters instead is process, discipline, and knowing how much uncertainty you can tolerate before it starts influencing bad decisions.

In an environment where many investors feel pressured to “do something,” this is a timely reminder that understanding risk, and starting small, is often the smartest strategy available.

Read it not as a cautionary tale, but as a framework for thinking clearly when markets stop making sense.

A lot can happen in one year.

In 1996, I sold my first company one year after I launched it.

My cut? $15 million.

I’d gone from zero to $15 million in one year. I felt like I’d won the lottery.

But then, suddenly, a weird thing happened: $15 million felt like chump change.

I start watching these guys make $100 million, $200 million, and I’m thinking, “What’s wrong with me?”

So I started taking on insane risks.

Fast forward a year, I’m at an ATM staring at $143.

I lost everything.

Fifteen million to $143.

How? It’s easier to do than most people think.

You do it by not understanding risk.

Most people don’t understand risk. The world would be a better place if we did understand it.

Risk is the single-most important thing everyone needs to understand.

That’s why I recently had Nate Silver and Maria Konnikova on my podcast.

If you don’t know them, they’re two of the sharpest minds on probability and human behavior.

Nate Silver’s the guy who brought data analysis to politics.

Maria Konnikova took on poker to understand how luck and skill intertwine—she started with zero experience and ended up winning big at the tables.

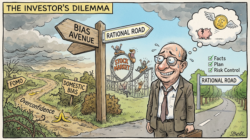

They both agreed on one thing: most people get it wrong because they don’t separate risk from uncertainty.

They think they’re interchangeable, but they’re not.

Here’s the thing about making decisions: we’re constantly waiting for all the information, that perfect moment of clarity when we finally feel “ready.”

But that moment isn’t coming.

If you want to get good at decision-making, you’ve got to embrace the idea that you’ll almost always be working with incomplete information.

Rather than letting that paralyze you, just jump in.

Poker players get this.

They’re used to acting on intuition, piecing together small clues, and accepting the inherent uncertainty of the game. And, really, life isn’t that different.

Try jotting down what you *do* know about a situation next time you’re stuck. Making a list of the known variables can clarify your next move and keep you from getting bogged down by all the unknowns.

BUT there’s a caveat: Start small.

I wish I’d started small after I sold my first company. Instead, I was throwing money everywhere.

Maria’s approach to this was personal.

She talked about how poker shifted her thinking about risk in everyday life, transforming her from a cautious player into someone who could handle a bit more chaos.

It’s not about flipping a switch and suddenly becoming fearless. It’s about easing yourself into risks that push your comfort zone, but don’t paralyze you.

So start small.

If you’re risk-averse, don’t go for the home run on your first swing. Instead, take small risks and build up your tolerance over time.

The experience will help you get comfortable with uncertainty, and over time, you’ll learn to weigh risk versus reward in a way that feels right for you.

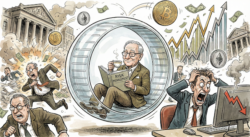

One of the biggest takeaways here is to stay process-oriented, not outcome-oriented. It’s so easy to judge a decision by its results, but Maria and Nate argue that’s a mistake.

Even the best decision-making process can lead to a bad outcome—it’s just how probabilities work. When things don’t go your way, don’t immediately think you screwed up.

Instead, focus on whether you made the right decision with the info you had. If you did, that’s a win, regardless of the outcome.

There’s a LOT more tips and tricks like this in the full podcast.

It’ll change the way you view risk EVERYWHERE in your daily life.

Click here for the full conversation.

Best,

James Altucher

Contributing Editor, Investor’s Daily

What you may have missed…

Was 2025 a year of inflection points in financial markets?

Long before tech unicorns were spotted hiding in every business plan, some families managed to get filthy rich. How did they do it? The second easiest way. Read more here…

The Underlying Malady

Almost all instances of imperial decline are accompanied by monetary decline, manifesting itself as inflation, corruption, and/or bankruptcy. But the real process is profound and mostly invisible. Read more here…

Bad Strategy

When leaders mistake short-term fixes for long-term strategy, the results are predictable: weaker markets, distorted prices, and growing costs for everyone else. Read more here…

What a $0.60 Stock Taught Me About Fear

A $0.60 stock. No good news. And a move Wall Street couldn’t explain. Here’s what panic really looks like—and how investors who understand market mechanics profit from it. Read more here…

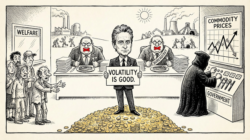

The problem with government is that it eventually runs out of other people’s money

The days of political promises and causes are over. We can’t afford whatever the politicians come up with next. We’ve run out of other people’s money. Read more here…