- Why academics make miserable investors

- The Berkshire Hathaway way

- Would you buy BP? All of it?

Investment strategies based on academic theories have a miserable reputation in the City. They manage to blow up financial markets as often as they manage to eek out gains.

Heck, one group of academics running a hedge fund even bankrupted a few national governments when their theory backfired. Yet the mathematical formula they used is still taught at universities today…

Part of the explanation for the poor performance of experts is that markets are cyclical while academics study the past. By the time academics cotton onto a trend, it is ready to reverse.

Thus academics recommended the 60/40 portfolio when bonds were yielding nothing. And concluded that dividend reinvesting is the key to good returns just when the boom in buybacks began.

I have my own theory why academics are so bad at investing. They are overspecialised.

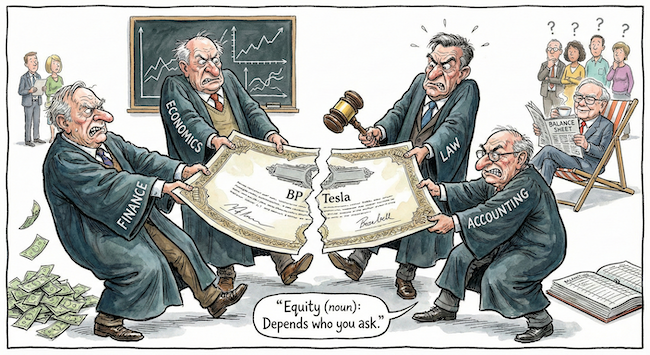

Back at university, I took a mixture of finance, economics, accounting and law subjects. One bizarre semester, the lecturers from each field asked us the same question on the first day of their classes…

“What are shares?”

Like all academics, they then set about answering their own question. But they all got it wrong.

At least, they each gave a completely different answer. Which would’ve been marked wrong had they taken each other’s exams.

To get good marks, I didn’t have to remember the correct answer. I had to remember who said what.

The finance lecturer explained that shares are a speculative asset. They represent a claim on a company’s future profits. These are paid out in the form of dividends.

A share’s value is determined by the market’s expectation of those dividends long into the future. It’s a perspective that only considers cashflow.

As the finance lecturer saw it, the point of stock markets is to make diversification easy. Instead of buying a company as an investment, shares allow you to buy a tiny stake in many different much larger companies. This is immensely advantageous because it reduces overall risk.

The accounting lecturer, by contrast, viewed shares purely through ownership and balance sheets. He explained that shares are a unit of ownership in a company.

If you own a business outright, you own all the shares. The stocks on a stock exchange just represent a slice of that ownership.

On an accounting balance sheet, ownership is referred to as “equity.” Which is why shares are also called “equities”.

The law professor would’ve called his colleagues charlatans. He claimed that shares are “a bundle of rights and obligations.”

I remember that quote so well because the professor ended up being my character reference for my Australian citizenship application. He had a genuine passion for teaching. But chose a field devoid of any passion whatsoever: corporate law.

As the law professor saw it, shares are nothing more or less than what the fine print says. Theory doesn’t come into it. You need to check carefully what you’re actually buying.

He gave us some extraordinary examples of how shares are not as commoditised or interchangeable as our finance professor liked to assume.

Financial markets are full of skullduggery. The legalities are how they catch out unsuspecting people. All the more reason not to punt the nation’s retirement savings on the stock market.

Last but not least was the most deluded of all – the economics professor. To him, shares were about who could access the returns due to capital. This requires some explanation…

An economy has four means of production. Land, labour, capital and entrepreneurship. Each is due a return. Labour gets wages, land gets rent, capital gets dividends and entrepreneurship gets a capital gain.

Shares and stock markets made it possible for workers to become their own capitalists, so to speak. The owners of their own workplaces. They can earn a return without having to work for it by saving and investing in shares.

Which academic was right?

I suppose you can decide for yourself who you agree with. But the point is that there are many different perceptions of the same thing.

I always wondered what would’ve happened if I got the four of them in the same room to argue it out. But no law professor would ever go near the business school. Nobody could understand the economist. Nobody cared about the accountant. And nobody trusted the finance lecturer.

As my career progressed, it became clear that the most successful investors balance all four perspectives.

The Berkshire Hathaway way

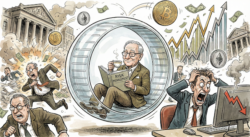

Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger were famously successful investors during their early years. They outperformed stock market indices by being very careful. Which is an unusual way to do well in finance.

Their methodology has been summarised in all sorts of mantras and books. But it’s noticeable that they align with all four understandings of “What is a share?”

First, Buffett is famous for saying that he invests in companies based on whether he’d be willing to buy the whole thing. He pretends it’s a small company that he’s considering buying all of. If he’d buy the whole thing, he’s willing to buy shares in the company.

This gets rid of the mirage that shares are something more distant than direct ownership in a business. They are not just a speculative asset promising cashflow. They represent the same rights and obligations of owning a company as someone experiences if they own the company in its entirety.

This makes an investor much more careful. It’s like saying that you should only buy a basket that’s so sturdy you’d be willing to put all your eggs in it. Too many investors today don’t pay attention to the basket they’re buying because they don’t plan to put all their eggs in it anyway.

Their way of thinking also got Buffett and Munger involved in the company’s management once they invested, as a business owner would. They knew what was going on on the ground.

Most investors today couldn’t name the CEO. Buffett knew what he had for breakfast.

It also made them investigate rather thoroughly for the details of owning a company’s shares. As my law professor would’ve advised, they checked the company’s fine print.

Most investors today don’t know what the companies they own shares in actually do.

Buffett and Munger believed most of the information they were looking for was hidden in the financial statements. That analysis is what they became famous for.

Of course, Buffett and Munger’s holding company Berkshire Hathaway didn’t often buy the whole company, let alone take it private. It was just about a mindset.

In practice, Berkshire Hathaway’s holdings were usually quite diversified. But only because there were a lot of opportunities to take advantage of. Still, the diversification benefit is real. But it can also be overdone.

No investor can manage a portfolio of more than 20 stocks to the standard of being a business owner in each one. The benefit of being careful about a few stocks is greater than the diversification benefit of owning too many.

Charlie Munger is famous for saying that the first $100,000 is the real challenge for an investor. Because it must be saved before investment gains can begin to take over. Compounding and investing can turn $100,000 into a good retirement.

That’s the economics professor’s point. Capital is due returns. But you have to be participating in it to compete. You have to have the capital to invest in the first place.

Inequality today is extreme because some people save and invest, while others don’t. Investing isn’t as hard as it can seem. The game is stacked in your favour. If you begin to play.

Which stocks are more equal than the others?

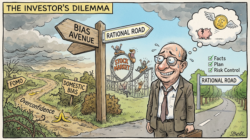

You now understand the four academic perspectives of the stock market. And how the world’s most famous investors applied them in practice.

My question to you is this: in which part of the stock market does your new understanding give you the greatest advantage?

You’re looking for a part of the stock market where companies are simple and easy to understand. Where the complexities of their legalities are not overwhelming. Companies you would be comfortable buying as a whole, owning for the long run, and overseeing…if you had the funds.

There is only one part of the market that fits the bill. Find out what it is here.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Editor at Large, Investor’s Daily

P.S. James Altucher is hosting a live briefing shortly that expands on several of the ideas touched on here — particularly where the most asymmetric opportunities are forming before they become obvious to the wider market.

James has a long track record of spotting these shifts early, often when they still feel uncomfortable or counter-consensus. In this upcoming session, he’ll explain how he’s approaching the next phase of the cycle and where he believes the biggest upside is quietly building.

Places are limited. If you’d like to hear James lay out the full case in his own words, you’ll want to reserve your seat ahead of time.